Ten nights in San Pedro de Atacama pass us by while we swing in hammocks and eat like cyclists, though it’s weeks since we’ve cycled. The package (Andy’s new Porcelain Rocket framebag to replace a broken Ortlieb one) was due to arrive 2 weeks before us and is still MIA. On our daily pilgrimage three blocks north to the post shop we learn that it’s not only not there, but we’re at the start of a long weekend, meaning it’s at best three days away. The thought of more hammock dwelling fills me with restlessness and I scour maps for nearby adventures and camping opportunities. I trace a road up Volcán Sairecabur to the north east, reaching a lofty height. Am I trying to over-compensate for this spell of laziness? Probably. I’m dismayed to be surrounded by all these huge volcanic peaks and not on any of them. A quick google later I’m unsurprised to find that the Pikes on Bikes have been there, done that and written the blog post.

Hammock life would soon look very appealing once again…

Hammock life would soon look very appealing once again…

We ask a few tour agencies about the state of the road, hoping there might be a slim chance a group attempting the summit could drop extra supplies of water for us near the top. The first company say they’re not going there as ice on the road is preventing them from getting to base camp. How far down is the ice? They don’t seem to know any details, and I wonder if it’s another tour company trick to divert all the people onto the same handful of tours. The second company say it’s doable and the road is rough but fine. However it will take a few days to organise as a local community has blocked the road – we’ll need to arrange their permission to pass. We decide we can ask their permission when we see them, and hope that when they see the poor cyclists that have hauled everything that far they’ll let us pass.

Loaded with 26 litres of water between us and four days of food my bike handles like a wet noodle. I feel like I’ve been robbed of my three granniest granny gears. I can’t believe people ride with this much weight all the time, and suddenly understand why so many people bemoan the rough dirt roads we seek out and stick to the pavement. Fair enough.

Water, water, everywhere, except in the desert around us

Water, water, everywhere, except in the desert around us

A road sign states our planned road is closed up ahead, but at this point we may as well plough on and see if we can get through. Just keep on pedalling, smiling and waving until someone stops us, is the general approach that’s worked for us so far. We see no more cars and eventually hit a section of utterly destroyed road. I’m convinced this is impassable by cars and so we happily pitch up meters from the road with a beautiful view down to the flat expanse of the Salar de Atacama. Of course, when a car does attempt to pass in the darkness of the early morning, it just means we’re kept awake for an hour while they shovel rocks and dirt and yell directions at each other. Although we’re in Chile now it seems the Peruvian rule of thumb still applies: Expect people to appear when you least expect them to.

The destroyed road and first camp

The destroyed road and first camp

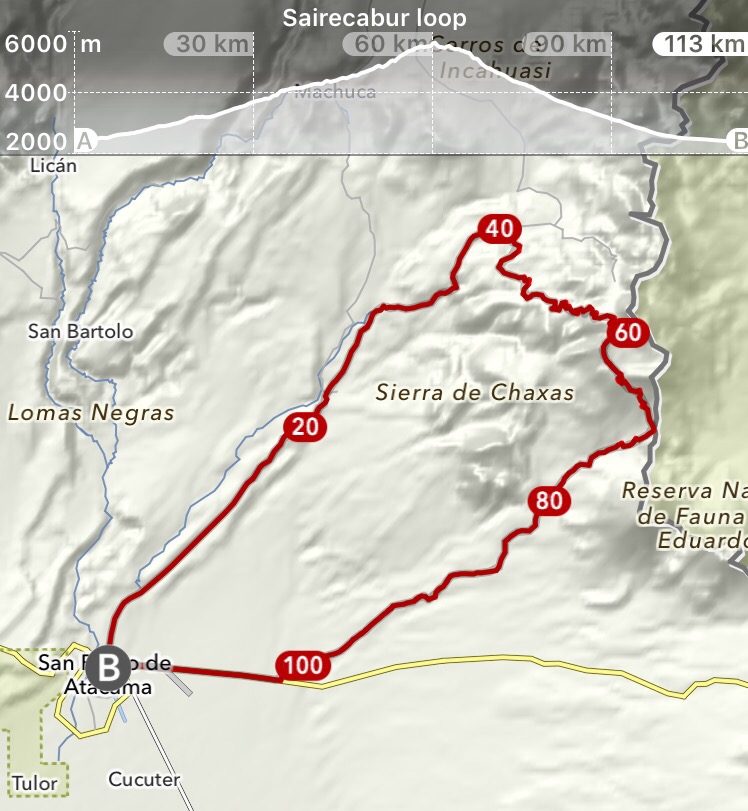

The road from San Pedro climbs continuously for 60km, gaining about three vertical kilometres in the process. Once we turn onto Sairecabur’s access road the surface is loose and sandy for the rest of the way up – the result of tourist jeeps that pack down the road surface now being in extremely short supply. We follow squiggly bike tyre lines up the sandy access road. For long stretches they are accompanied by plodding footprints. With so little traffic I guess they are months old. We follow them up, occasionally feeling smug when I see a continuous line of footsteps while I ride, but it never lasts long before I make my own. Wisely, probably, the trail stops at the penitentes, and that’s the last we see of them.

Sandy roads and a mysterious train carriage on the way to camp 2

Sandy roads and a mysterious train carriage on the way to camp 2

Ah, the penitentes. So novel initially, we pause at the first few patches by the roadside (around 5100m) to marvel and take photos. Soon enough we’re awkwardly pushing the bikes off-road to get around ever larger fields of them. The manoeuvres get increasingly awkward and energy-sapping as less and less of the road is rideable or even visible. But we’ve come this far and so we push on. If we’re forced to return the same way we know it’ll be a fast enough roll back to San Pedro, so we have enough time, food and water.

Penitentes filling up the tracks and the summit of Sairecabur looming about 600m above us

Penitentes filling up the tracks and the summit of Sairecabur looming about 600m above us

The terrain flattens out around 5500m and the 500m or so to the summit rise steeply from there. We had harboured hopes of continuing on to the summit on foot, but the state of the roads means we arrive at basecamp later than expected, making an awkward time for a summit attempt. With the state of the roads on the return loop being the big unknown factor we decide to leave ourselves plenty of time for that instead, and start the traverse skirting a massive crater. The next few hours are spent hauling the bikes through more penitente/snow fields, and I’m relieved not to have awoken to this little surprise. At the crater lip the view opens up to the perfectly conical Volcán Licancabur towering over the desert gems of the turquoise Laguna Verde and milky Laguna Blanca in Bolivia, just a handful of kilometres away. The thought of this view got me through many km’s of hike-a-bike, and it does not disappoint. Downhill progress ploughing through the slushy gravel of the long-unused road is slow, but not worryingly slow, so we call it a day after a mere 15km (new record for shortest day) to cash in on a scenic campsite while we’re still high.

Crater pushwhacking and descending on the other side with epic views of Laguna Blanca and Verde courtesy of Bolivia

Crater pushwhacking and descending on the other side with epic views of Laguna Blanca and Verde courtesy of Bolivia

Who am I to think I can google earth better than a Pike? (Known to be masterful route creators) They descended into a dead end surrounded by steep cliffs, resulting in an extra night. This thought keeps me up at night, wondering if I’ve mapped out all the options for the next day’s descent, or if we’ll be stuck in the desert for what might be a thirsty, waterless night. As it turns out my wayfinding isn’t the problem, but the roads most certainly are. At first it’s comically lumpy riding, but before long there’s very little riding to be had and we find ourselves once again taking the bikes for a stroll. I ponder the increasing frequency of this situation on our chosen routes but struggle to explain the masochism. Hauling the bikes through some ridiculous excuses for roads it takes a full day to make our way back to San Pedro. It’s miraculous we don’t suffer any punctures on the way, dragging our bikes through all sorts of vicious, spiky looking things and over sharp rocks. Many of the roads are totally washed out (with what water I’m not sure) resembling more a rocky riverbed than any kind of road. For once, I think, it’s possible to legitimately say a Surly Icecream truck would not be overkill. Exhausted, on reaching San Pedro, it’s straight to the bottle shop for some celebratory beers. One adventure I don’t regret, but am in no hurry to repeat.

The state of the ‘roads’ on the descent got pretty… interesting

The state of the ‘roads’ on the descent got pretty… interesting

Route notes

Download the GPX file (note this is not recorded but made from waypoints)

Download the GPX file (note this is not recorded but made from waypoints)

Firstly, we can’t wholeheartedly recommend this route. It’s beautiful but an absolute slog with large unrideable sections. Fellow masochists, read on…

Water: We hauled all our water (3 nights, 4 days) after reading the penitentes may be contaminated by the presence of old sulphur mines. While we did pass patches of sulphur, I suspect you could get water from penitentes with some care. You’ll need plenty of fuel obviously. Penitentes were present upwards of about 5100m

Timing: we rode this over 4 days in early October and had to get through many pentitente sections. This is mainly problematic on the return track after the crater where sections of the road were completely covered. Had this been any worse, getting past would have been extremely difficult.

Route finding: the way up is easy, the way down needs some care. Study satellite imagery and preferably have it cached so you can refer to it on the ground, we found this useful. The tracks back down haven’t been used by vehicles for some time which will become clear when you see the state of them. Many sections barely resemble roads and are washed out and badly rutted. You’ll need to carry your bike through/out of deeply eroded areas. Give yourself a day for the descent after the crater. The key waypoint is around 22.861957 S 67.978899 W where we took an unintuitive and easy to miss right turn and crossed the riverbed to avoid being funnelled into the dead end peninsula.

Obviously you’ll need to be very well acclimatised to attempt this. We spent nights 2 and 3 camping around 5000m. If you’re going to attempt the summit you’ll likely need to spend a night at about 5500m.

You’re unlikely to encounter anyone to help you out on this route, particularly on the descent.

ace!

Hi Guys,

Just read your trip up Sairecabur. It appears you were probably following our tracks for a while. we were there in late July 2017 with a lot more snow around. We didn’t get the job done, but enjoyed the outing immensely.

https://www.crazyguyonabike.com/doc/page/?o=1mr&page_id=516936&v=K5

Regards

Safe cycling

Peter

Hey Peter, thanks for sharing your post, it was great to read it! We also didn’t finish the job quite as intended, but as you say, it’s an incredible place to get to spend some time. Probably one of the adventures that I think of most often. Happy trails.

Pingback: 033: San Pedro De Atacama